The Swedish polymath Per Georg Scheutz (1785-1873), who worked as a lawyer, publisher, journalist, translator, and inventor, was born on 23 September in 1785. He was the first in the world to build Charles Babbage’s Difference Engine or its simplified variant to be more exact.

He studied law at the University of Lund, received his diploma in 1805, and started to work as a lawyer. In the 1820s, Scheutz became the co-editor and later on the owner of one of the most significant political newspapers in Sweden. He had also earned renown for his translation of works by Shakespeare, Boccaccio, and Walter Scott, before his interest focussed on mechanical engineering. Among many other things, he was the publisher of a dozen of technical and commercial journals. He was knighted by the Swedish King in 1856, and was accepted as a member of the Royal Swedish Academy of Sciences.

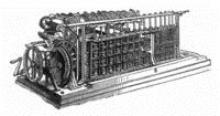

By taking a pioneering role, he is best-know for his achievements in computer science. He was the first one to construct a simplified difference engine that calculated using fourth-order difference instead of the original six orders of difference. The machine used numbers of fourteen digits, and was capable of calculating and printing tables. It was put on show in London in 1854; Babbage himself warmly welcomed the project.

Scheutz and his son, Edvard, read about Babbage’s Difference Engine in the Edinburgh Review in 1834. The article inspired the two of them to set about constructing a substantially modified and simplified version. The prototype of the machine was operational in the same year, but their ideas were little supported until 1851. Then, however, the Swedish Academy of Sciences approved their initiative, and provided financial endorsement so that they could build a machine that was larger in size and better in function. Construction was completed in 1853, and the machine won the gold medal at the Paris World Exposition. By the time construction was completed, Scheutz had almost gone bankrupt.

A faithful copy of the machine was produced by Messrs. Dunkin and Co. for the British government, and it was used in the archives of the British General Register Office. It came into the possession of the Chicago-based Felt and Tarrant Co. in 1924, and later on it was acquired by the Smithsonian Institute.