It is the birthday of the Hungarian poet Attila József, which is observed as the National Poetry Day in Hungary. This is a day for all of us to celebrate that at some point in time, somebody developed an information compression (or even coding) method, which we normally refer to as poetry. Perhaps what we mean by poetry is the intensive totality of lyrical poems or the way of composition, which condenses true words and expressive images into poems: the sea of reality into a single drop of a poem.

It seems secondary what means of conveyance is used in the compression process of writing poetry: stone slabs, parchment, paper or a computer. This is the development curve written culture has taken, but poetry already existed earlier, which people sang and taught to each other. And poetry will exist even when the superiority of written words is constantly challenged by new sort of experiences from visual stimuli to virtual reality.

However, the means of conveyance fundamentally determine our ways of producing and using culture: to what extent and how easily our ideas can reach others. Today, it is a significant challenge to museologists that poets do not (necessarily) use a pen and paper for writing poems any longer. What will be stored as the heritage of a poet in a literary museum? A computer hard drive? A pendrive? A cloud? Thus manuscripts take on a new understanding in the world of digitally produced documents.

There was a time when the realms of "sciences" and "humanities" were treated separately, but we regard them as one in terms of cultural history, and we also know that computer capabilities have been utilised in areas related to written words since the initial stage of Hungarian computer science.

László Kozma, the designer of the first Hungarian electromechanical computer called MESz-1 completed in 1958, was working on a "calculator service" accessible on telephone lines already in the 1940s, which reveals what a genius mind he was. No wonder that he was soon delegated a task that was related to poetry.

Here is an excerpt from Győző Kovács’s article in Magyar Tudomány:

"After the completion of MESz-1, László Kozma worked for the Research Institute for Linguistics of the Hungarian Academy of Sciences from 1960 to 1964, where he, together with with Béla Frajka and department staff, built an automaton with relays and vacuum tubes. The machine was built to do language statistics so it can be seen as a special purpose computer in today’s understanding. The machine stored text on a 5-channel punched tape, which was sent and read by a teleprinter, and analysed according to nearly eighty criteria. (For instance, the alteration of words with long and short syllables or the ratio of vowels and consonants in Himnusz, the Hungarian national anthem; or the machine was able to compile a list of 1000 words that are the most frequently used; and helped in identifying which parts in the Bible were written by the same author, etc.)"

From the recollections of Győző Kovács, we also know that the M-3, the first Hungarian electronic computer, did similar language statistics on the poems written by the Hungarian poet Árpád Tóth.

And today it is evident that literary scholars draw on databases in their work. This was not always the case. RPHA, the first relevant Hungarian literary database, processed old Hungarian poems. Iván Horváth, the creator of the database, did not even use a real computer initially, all he could rely on was an edge-punch-card sorting system.

It is thanks to Iván Horváth that we have the world’s first textual criticism published on the internet, which illustrates to what extent our idea of a book has been changed by the internet, and what vast opportunities hypertext can offer. We are talking about a time that was twenty-five years ago and we still fail to make good use of all these possibilities. It is the intitial phase of a process that we experience. Printed books with spaces left for initial letters to be painted by hand were made as imitations of hand-written codices for a long time.

(This might make many Hungarians remember the TV commercial of the KODEX-2000 word processor machine in the 1980s:

"The task has not changed much in a thousand years…")

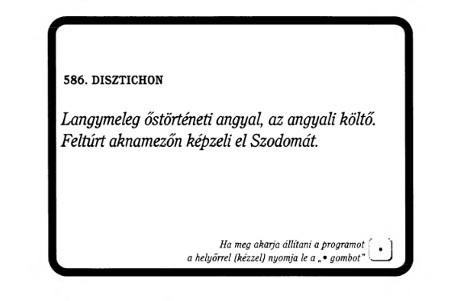

As to poets, a great number of them have no aversion towards computers. For instance, Tibor Papp, the Hungarian poet living in Paris, contributed to editing Alire (1989), the very first digital literary journal, and engaged in using a computer in his poetry with amazing creativity. He realised how poetry could be enriched drawing on combinatorics. He created Disztichon Alfa, a text-generator in 1993, which generates billions of metrical poems, mostly funny and provocative. These perfect distiches are created by Tibor Papp as the programme he himself wrote uses the database of words he has created when parts of a distich are put together. Only a fragment of the generated poems could be printed since the complete work printed out would fill airplane hangars. When we read these distiches on an Apple Macintosh, we are probably reading a distich that no human eye will ever see again. And here comes the next on...

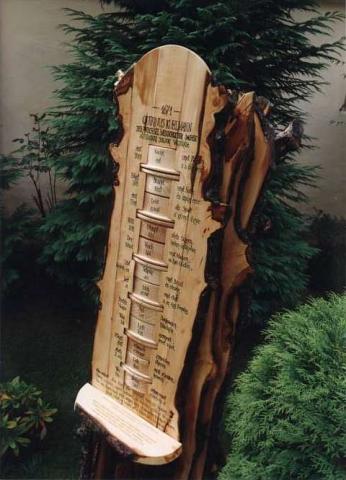

Tibor Papp revived a literary tradition that goes way back in time (since even in early modern times there were attempts at combinatory poetry, moreover, a sonnet composing automaton had been created using discs carved out of wood), and found an ideal setting through the computer. Being a prominent avant-garde poet, Papp also used the computer to broaden the range of sound poetry and picture poems, which is best exemplified by his work entitled Hinta-palinta.

The ouvre of Tibor Papp may as well belong to the literary past of the future: it reveals all the possibilities artists have not used so far: the play with infinity.

While Papp uses the computer in an attempt to widen the range of methods and techniques in creating poetry, other poets draw on computer use as a theme:

"Feleségem monitorján három csetbox van nyitva,

[Three chat boxes are active on my wife’s screen,]

boldog, kinek küld egy szmájlit kék-fehér kis ablakába kattintva.

[Happy is the one who gets a smilie with just a click on the little white and blue box]

Én meg csak itt búslakodok magamba,

[And I feel so sad and lonely on my own]

senki nem ír az üzenőfalamra,

[’cause no-one posts anything on my message board]

úgy kisírom emiatt a szemeimet, kisangyalom, reggelre,

[Tears stream down my face and in the morning]

hogy a facebookon még a saját asszonykám se taggel be."

[not even my woman will feel like tagging me in on facebook]

- writes Dániel Varró in his poem Feleségem ha felmegy a facebookra [When my wife logs into facebook], which mocks community media users, "grammar nazis" or users who share photos of kittens.

The heritage of poets from earlier times and the innovations, in terms of form and content, of new poets are equally important. We should share as many poems as possible on Poetry Day (and not only on this day) since poetry never divides but bonds us together. And we can take it for granted that poets will continue to be our companions amidst the development information and communication technology devices are about to undergo in our extremely rapidly changing world.

Gábor Képes