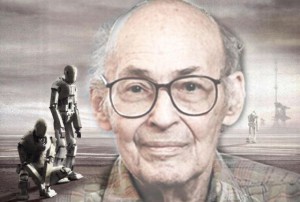

At the age of 88, Marvin Minsky, one of the great pioneers of artificial intelligence research, passed away on 24 January. He died of cerebral haemorrhage. He laid the foundations for the field, and made no compromise by adhering to the original, classic concept throughout his life: he put focus on the big whole instead of partial results achieved in various scientific disciplines.

At the age of 88, Marvin Minsky, one of the great pioneers of artificial intelligence research, passed away on 24 January. He died of cerebral haemorrhage. He laid the foundations for the field, and made no compromise by adhering to the original, classic concept throughout his life: he put focus on the big whole instead of partial results achieved in various scientific disciplines.

In an interview, Isaac Asimov said that there were only two people he would admit were more intelligent than he was. One was Carl Sagan, astronomer and astrobiologist, the other Minsky. It is also Minsky who is respected as a mentor by Ray Kurzweil, the polymath inventor (speech recognition system, electronic music instruments, technologies to aid the communication of the blind, etc.), the advocate of Google machine learning and natural language processing, and the guru renowned for his perplexing visions of the future and Singularity.

Minsky, who combined a scientist’s thirst for knowledge with a philosopher’s quest for truth, gave inspiration, directly or indirectly, to a great number of developers in the fields of personal computers, the internet, microprocessors, and supercomputers. Without him, the worldwide web would be different from what it is and less advancement would have been made in the fields of AI, machine learning, and recognition technologies.

In the summer of 1956, researchers of neural networks, automatons, and related fields, among them, Marvin Minsky (Harvard), Nathaniel Rochester (IBM), John McCarthy (Darthmouth College), and Claude Shannon (Bell), who elaborated information theory, met at Darthmouth College (Hanover, New Hampshire) to work on a two-month project on artificial intelligence. This event was the birth, the zero year for artificial intelligence. (The term itself was coined by McCarthy.)

Although no breakthrough of worldwide significance was made, and the contributors were few in number, the project involved exactly those who were to influence and shape AI trends in the forthcoming two decades.

In 1959, Minsky and McCarthy established what was to become today’s Computer Science and Artificial Intelligence Laboratory (CSAIL) of MIT. This is where the principle of the free flow of digital information was formulated that would lead to the open-source software movement.

However, Minsky already put the stamp on the field as a student of Princeton when he and a fellow student designed and built the first neural network computer or learning machine, the SNARC. Three thousand vacuum tubes and the autopilot of a B24 bomber helped SNARC to simulate a neural network of 40 neurons.

Legends claim that it was one of Minsky’s study (written in collaboration with Seymour Papert) two decades later that had great importance in driving away trickling government funding from the research of neural networks. Reasons, on the one hand, included the absence of scientific rigour in relevant research work, on the other hand there was a recognition that a great deal of important problems could not be solved with simple networks.

SNARC was not the only invention Minsky had. In 1957, he designed a special microscope that would map a selected plane inside an object instead of the surface of the object – a forerunner of today’s confocal scanning microscope. In 1963, he designed the first head-mounted graphical display, which was to become the distant originator of virtual reality headsets. Minsky also made a minor contribution to music history in 1972 by designing, in collaboration with Edward Fredkin, a synthesizer called Muse, which was used by electronic musicians in Philadelphia in the ’70s. He also designed mechanical hands with tactile sensors, which had great impact and advanced robotics. The theory of frames, an early version of object-oriented programming, is also linked with his name.

Published in 1985, The Society of Mind, a scientific bestseller where “AI meets MTV”, is the main work of his lifetime. In his book of unusual structure, he revisited his favourite topic by trying to describe how the brain works. He saw the mind as the combination of gigantic numbers of semiautonomous and unintelligent agents in a system. But how can consciousness emerge in the absence of intelligence?

According to Minsky, all phenomena are physical, and humans are extremely complicated machines. However, the idea of a machine needs to be re-defined in this case, and applied not only to lifeless objects but to the brain as well. Imagine replacing each cell in a brain with a computer chip designed to perform the same functions and connected to the other chips exactly as the brain cells are connected. Minsky argued that there was no reason to assume that the substitute would work in a different way from the original.

The public had to wait more than twenty years for the sequel to The Society of Mind. Published in 2006, The Emotion Machine outlined the future of AI, and analyzed emotions understood as a way to think. Rooted in the field affective computing at MIT, Minsky’s idea is that emotions increase intelligence, but emotions are used to seek ways to think for answers to problems different from problems logical thinking is used for. The rule-based mechanisms of the brain “turn on” emotions when such problems are encountered.

The past of the future

To protect the values of the past, to adapt to the present, to influence the future.